My last articles considered low-stakes cash game preflop play from early and middle positions, where the basic philosophy is to “play tight and don’t call preflop raises.” When we play this way from the first five positions on a 10-handed table, we are usually seen as a rock, which is a great image to have when we open up our game in late position (hijack and cutoff) and the button.

“Don’t challenge strong players, challenge weak ones. That’s what they’re there for.”

– John Vorhaus

Playing the Late-Position Game

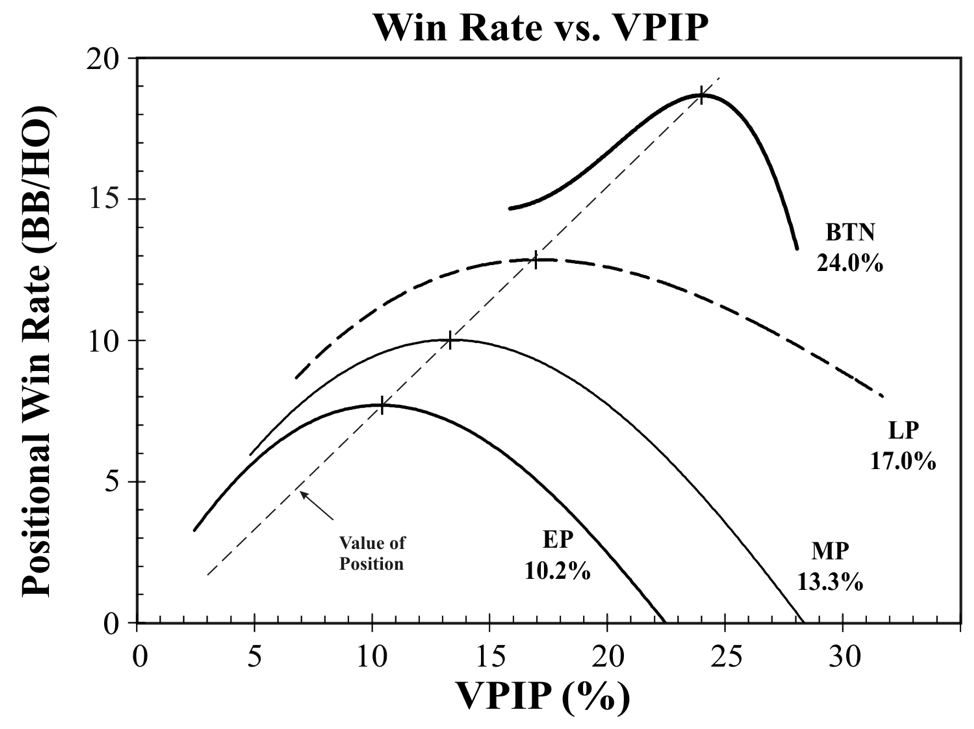

We previously acknowledged the huge value of position by studying the online EP and MP curves in Figure 1. Now let’s look at the LP curve, which is for the hijack and cutoff, the two seats before the button. The peak LP profit is about 13 BB per 100 LP hands dealt, with an “optimum” VPIP of 17 percent. So our improved position not only allows us to play a wider range, we can also make much more profit doing so.

Optimal button play is just an extension of this. Since only the blinds are behind us preflop, and since we will always have superior postflop position, the button is the premier position on the table. Consequently, we can play an even wider range of hands while achieving even greater profit.

Our Vegas $1/$2 Late Position VPIP Target

The peak online button profit is at VPIP = 24 percent, with a much higher profit of 19 BB per 100 button hands dealt. Since we can play even more hands in a Vegas $1/$2 game, we can probably extend our VPIP target stat to at least 30 percent for the Vegas game.

Vegas $1/$2 often provides opportunities that are rare in online games. For example, since preflop raising is less common, we see more unraised pots on our button, allowing more playing opportunities. The Vegas game also has a lot more limping, so we often have better implied odds than we do in the online game. Finally, the Vegas game has a higher fraction of weak players to exploit, and the button is the best place to do it from.

My Baseline Preflop Ranges

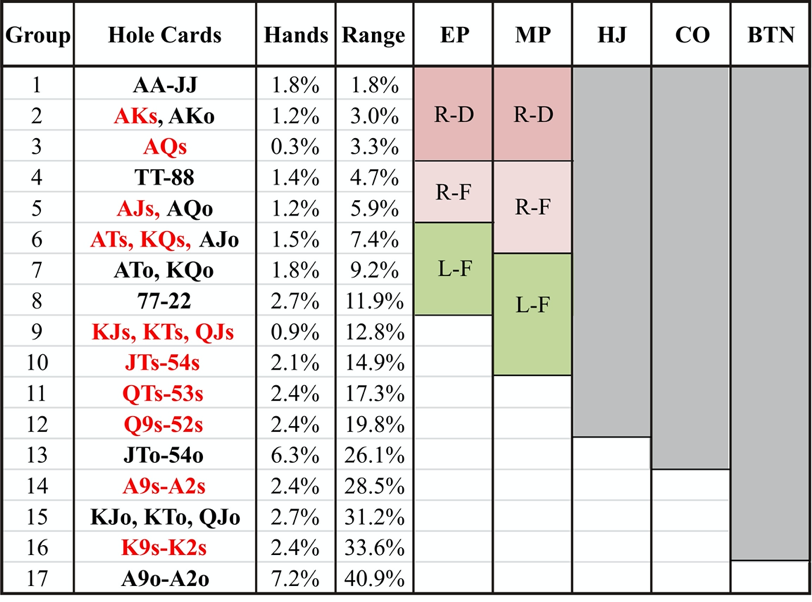

So our baseline VPIP stat targets are 20 percent (HJ), 25 percent (CO) and 30 percent (Button). But since we will fold some of these combos when we face a raise, our baseline playable range from these positions must be somewhat wider.

The shaded region of Figure 2 depicts my own starting hand preferences. I have arranged these combos into various groups, such as small pairs (Group 8) and suited king-rags (Group 16). I then ranked these groups in their general order of strength for a typical Vegas $1/$2 game (in my opinion). We can quibble about which combos to include in these ranges, but my choices are based on the hands I think play best in a very loose and passive Vegas game. This chart is also designed to be simple and easy to recall at the table.

For example, it should be clear that suited connecters are stronger than suited 1-gappers, which are stronger than suited 2-gappers. So that is how Groups 10, 11 and 12 are ordered. But I also believe that suited 2-gappers are stronger than unsuited connectors for this game. (I use some math to justify this conclusion.) So, unsuited connectors are ranked lower.

I believe that each of these groups is stronger than the suited ace-rags. This is because our Vegas villains often limp with hands as strong as AK and AQ. This makes a hand like A6s very difficult to play when we flop an Ace or a six, even when we have superior position. But a suited one-gapper can also flop a straight or straight draw, and those draws are usually hidden. Unsuited ace-rages (Group 17) are even weaker, which is why they are at the bottom of this chart.

Perhaps, surprisingly, I place the unsuited Broadways (Group 15) far down my list. This is because they rarely flop straights or good straight draws, and flopping a king, queen or jack presents very dangerous reverse-implied-odds difficulties post flop.

One way to look at these rankings is that I prefer combos that are easier to play aggressively postflop. So I prefer combos that are more likely to flop a big hand (two-pair or better) or a big draw (8-outs or better). We are far more likely to be paid off when we succeed with these hands, which makes them more valuable than they would be in an online game.

The combos that flop easily dominated one-pair hands against players who like to limp with stronger hands are far more difficult to play postflop, so I discount them, especially the ace-rag hands.

You may disagree with my choices, promoting some combos and demoting others. Feel free to create your own chart, ordering combos and groups as you choose.

Conclusion

Limited space here doesn’t allow for a full description of the reasons behind my starting hand choices. (A detailed discussion can be found in Donkey Poker Volume 1: Preflop.) But it’s clear that we should loosen up considerably once we reach the best three positions on the table. With superior postflop skills, we may be able to play even wider ranges, especially in special circumstances that are common in live, low-stakes cash games.

You don’t need to follow this chart — feel free to create your own. Having a pre-defined baseline has important advantages. Having thoroughly analyzed your baseline preflop strategy, you know this strategy is sound. This helps to maintain your discipline and enhances your confidence, which helps your bottom line.

And a pre-defined baseline frees up your mental capacity to focus on what your opponents are actually doing.

Steve Selbrede is a retired Silicon Valley engineer living in Las Vegas. He is the author of six poker books, including his most recent Tournament Poker for the Rest of Us (presented by CardsChat). The charts in this article come from his book Donkey Poker Volume 1: Preflop.